Why should we care about air leaks and infiltration in our homes?

We lose up to one third of the energy we buy through holes in our houses.

That stat was published in 2012 by the good folks at Fine Homebuilding and the Building Science Corporation, but it remains largely true for many existing homes around the country today. The average age of houses in the US is 46 years old. So while we now know better, we still occupy many structures that are deficient. A third of our utility bill. A little stunning to hear, isn’t it?

How did we not know this?

Well, energy used to be cheaper. And we have learned that cheap energy provoked environmental burdens that aren’t sustainable anymore. Further, scientists started looking into the conditions that degrade homes as technology and preferred building materials changed.

Traditional exterior wall assemblies had been vetted over the years through raw empirical experience, eventually yielding generally successful building strategies. While they weren’t the highest performing systems, they were in many ways the least problematic.

We could live with the low performing insulation by stoking the fire in winter even if we could feel a slight wind at the window; or we could install exterior awnings over windows that oppressively heated a space in summer. With technological advances and new materials available to make new building facades, we started to solve some of these issues only to encounter other long term implications of how those assemblies performed.

As researchers dialed in on the small details, they learned that reducing air infiltration (and air leakage) resulted in reduced energy costs. It turns out that stopping air is the second-most-important job of a building enclosure after controlling for water.

Air leaks and infiltration damage the building shell by transporting moisture, which causes condensation, rot, and mold inside the exterior walls. Additionally, air moving through the structure carries energy with it: your air-conditioning or heating bills end up reflecting this unseen drain of energy.

What exactly causes air leaks and infiltration?

Simply: pressure differentials.

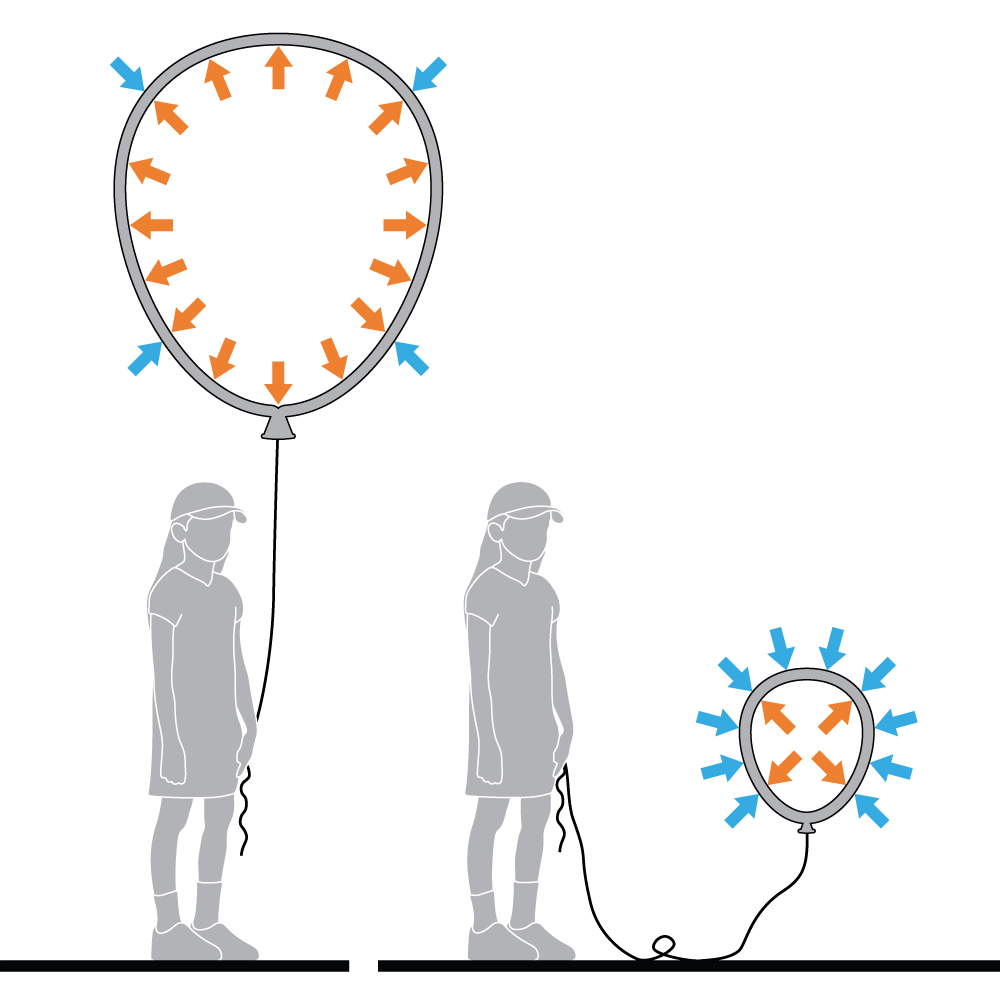

Imagine a balloon. You blow it up only to see that the next day it is half the size. The air has leaked out; it is unclear how…the knot is still tight, but clearly the balloon is smaller.

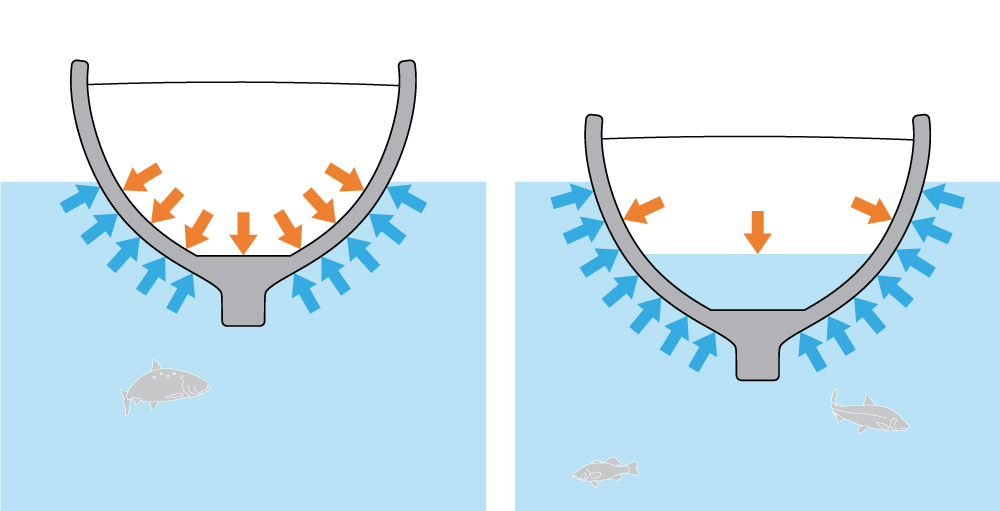

Or, imagine an old wooden boat sitting in dry storage. You decide to set it in the water one day, and the next, it’s a little low in the water.

Each of these conditions of pressure illustrates the continuous forces on every nook and cranny of the balloon’s and boat’s surfaces. The relentless pressure finds all the weak spots, leaking through by small amounts over time.

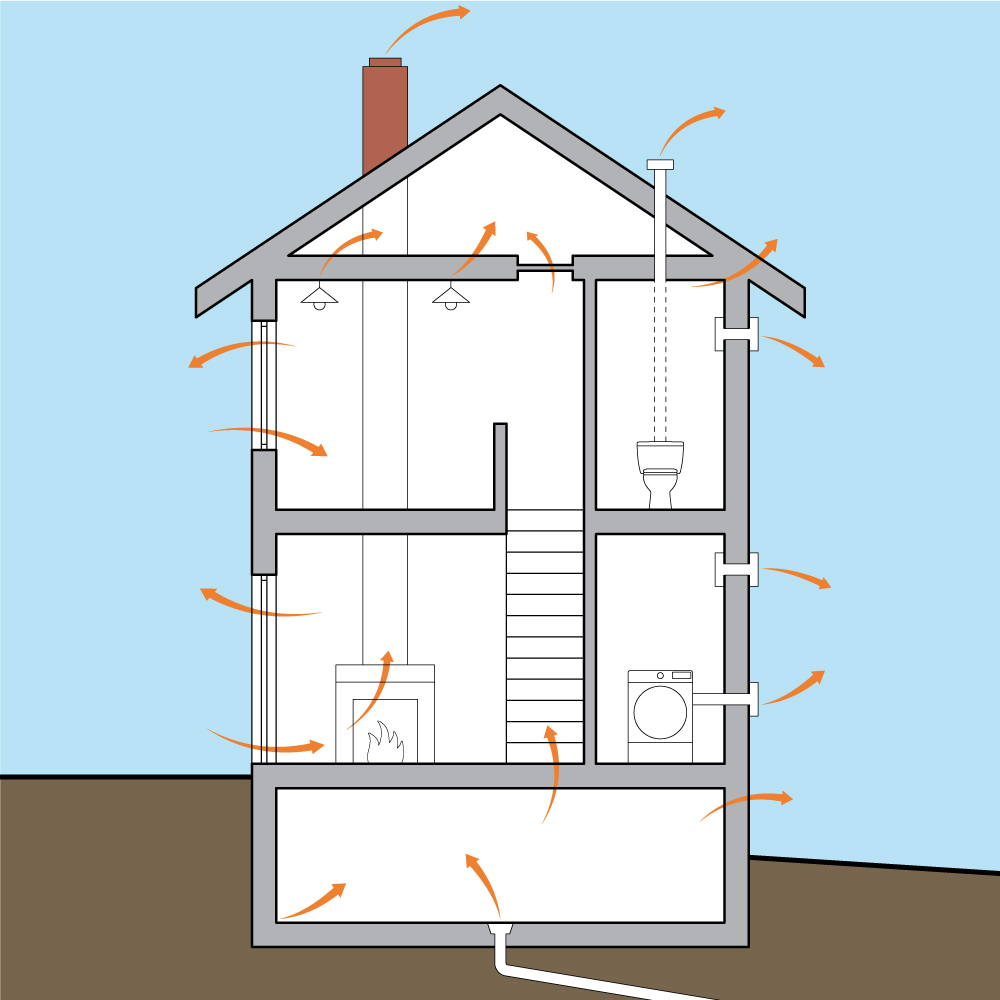

In a leaky house, air pressure (created by exhaust fans, the stack effect, and/or wind) pushes through the floor, walls, and ceiling. Direction of flow (inside to outside or outside to inside) can change depending on season or locale or mechanical conditioning.

Can air infiltration and leaks be measured?

Yes! A blower door test can determine the quantity of air exchanged between the indoor (conditioned) and outdoor (unconditioned) spaces. First, a fan is located in an exterior door frame where it sucks air out of the home. Then, a pressure gauge measures how air rushes back into the remainder of the house via the various gaps and cracks. (The test can also be reversed.) A blower door test can be part of your remodel or addition as one of the options for a required energy measure in Oregon.

Where do air infiltration and leaks occur?

Common areas where air infiltration or leaks occur:

- Intersections of materials — Materials are rarely fitted so tightly that air cannot pass. Further, joints can change size as building materials change temperature. And it is a open secret that sealants have limited lifespans to block open joints.

- Penetrations in the envelope — Openings in the building shell create gaps, such as at window and door seals, chimneys, bathroom exhaust fans, ductwork, and wiring penetrations.

- High and low weak points in the building shell — At lower levels, basements and crawlspaces, we often see infiltration. At upper floors, chimneys and attics, we often see leaks. These weaknesses illustrate the thermal movement of the stack effect (cooler spaces lower / hotter spaces higher). This interior thermal movement induces pressure differentials at the various micro holes in the envelope.

We need to tighten up our houses.

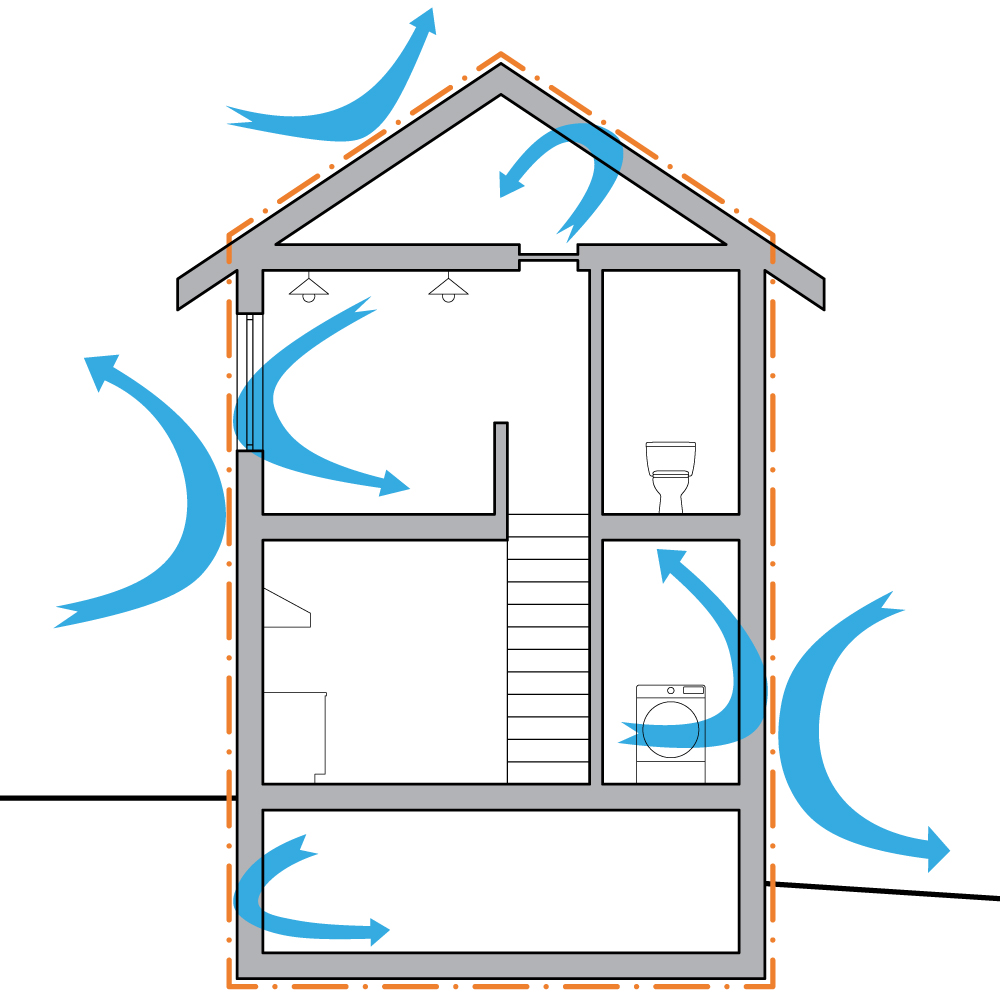

By closing these holes in the building envelope, we can control the energy losses and improve the durability of the building materials.

So how exactly do we tighten up houses?

- Air barriers—What are they?

An air barrier (discussed in our Perfect Wall post) is a continuous membrane that overlaps the various joints and gaps in the building materials. It can be a sheet with taped joints, or a liquid-applied membrane that is continuous around the shell of the building. Seal the air barrier to openings like windows, doors, and other smaller penetrations like exhaust vents, wiring conduit or piping.

Canada recognized the importance of an air barrier in its national building code 25 years ago. In the United States, it was absent from state energy codes historically and just recently added as we catch up to modern understanding of building science. Oregon’s residential code didn’t add air sealing beyond window and door joints to include air barriers until the 2021 ORSC update.

Given its fundamental positioning in the building enclosure assembly, adding an air barrier is best done during a new build or a fairly extensive exterior remodel.

- Improved mechanical ventilation—what does that mean?

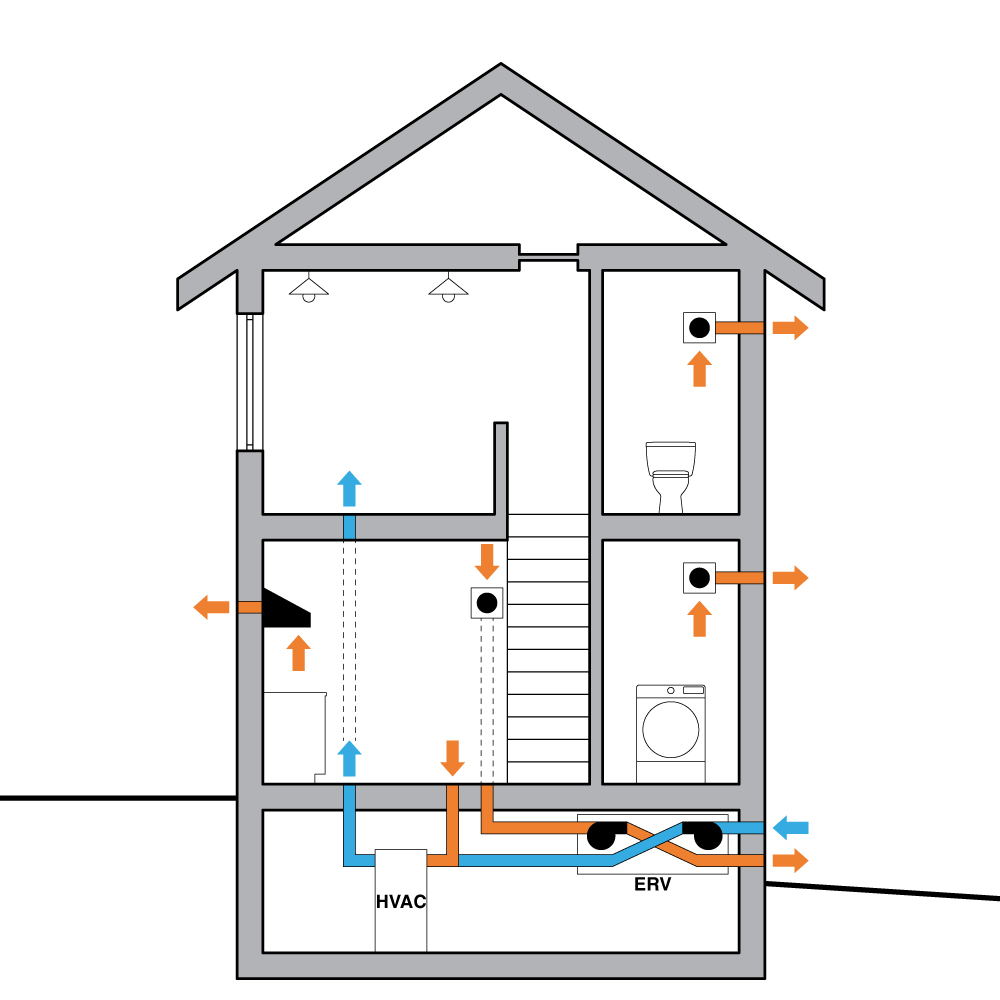

An improved mechanical ventilation system incorporates a fresh air intake and tempers that air for moisture and heat when appropriate to the season. For instance: an electric heat pump paired with an energy recovery ventilator (ERV). A separate dampered fresh air intake balances the building air pressure change when we run the kitchen hood exhaust.

Doesn’t a house need to breathe?

Some outdated builders think this tighter building strategy causes rot and mold, which it certainly could if applied incorrectly. Familiar with the old, lower-performing building traditions, they say, “A house needs to breathe.”

But that mindset puts us back into paying the 30% energy premium to condition a house that will degrade faster over time because of the leaks.

“A house doesn’t need to breathe; it needs to dry.” – Pretty Good House

We still need air circulation inside the new tighter volume—humans typically need to breathe! And those pesky humans also create humidity (sweating, bathing, cooking). Interior mechanical ventilation relieves this humidity and adds fresh air in a carefully controlled way, not just sucking whatever filters through the gaps in construction. And this ventilation system uses less energy overall because it’s not oversized to account for leaks lost through the shell.

Meanwhile, what can I do to reduce air infiltration and leaks on my existing home?

- Apply foam sealant, with professional input, to areas where air movement can be felt.

- Examine and replace deteriorated exterior door seals and thresholds.

- Check windows to make sure they are locked and window seals are intact.

- Minimize opening and closing exterior doors during extreme seasonal temperatures.

- Seal gaps around supply-air ductwork and floor connections in uninsulated crawl space and basement areas.

- Examine bathroom exhaust fans with the back of your hand. Seal gaps/spaces around the exhaust fan housing & replace backdraft dampers if needed.

- Call your local friendly neighborhood architect to see how to save energy during your next remodel or new build.